甲壳纲动物

编辑甲壳纲动物(甲壳纲)形成了一个庞大而多样的节肢动物分类群,包括蟹、龙虾、小龙虾、基围虾、明虾、磷虾、木虱和藤壶等常见动物。[1]甲壳纲动物群通常被视为亚门,由于最近的分子研究,现在人们普遍认为甲壳纲动物群是并系,包括除六足动物以外的泛甲壳动物。[2]一些甲壳类动物与昆虫和其他六足动物的关系比它们与某些其他甲壳类动物的关系更密切。

甲壳纲动物所描述的67,000个物种,大小范围从0.1毫米(0.004英寸)的Stygotantulus stocki到足展近3.8米(12.5英尺)且质量为20千克(44磅)的日本蜘蛛蟹。像其他节肢动物一样,甲壳动物有外骨骼,蜕皮生长。它们有别于其他节肢动物群体,如昆虫、多足类和螯肢动物,因为它们拥有双肢(双肢型)和其幼虫形态如鳃足动物和桡足动物的无节幼体阶段。

大多数甲壳动物是自由生活的水生动物,但有些是陆生动物(如木虱),有些是寄生动物(如根头类、鱼虱、舌虫),有些是固着动物(如藤壶)。甲壳动物有着大量的化石记录,可追溯到寒武纪,包括三叠纪以来一直明显未变的蟹形鲎虫等活化石。渔业或农业生产了1000多万吨甲壳类动物供人类食用,其中大部分是基围虾和明虾。磷虾和桡足类没有被广泛捕捞,但它们可能是地球上生物量最大的动物,也是食物链的重要组成部分。甲壳纲动物的科学研究被称为甲壳动物学(或者,软甲动物学、甲壳类动物学或甲壳类学),从事甲壳动物学研究的科学家是甲壳动物学家。

1 结构编辑

甲壳纲动物的身体由几个部分组成,这些部分被分成三个区域:头部、[3]胸部 和腹部。[4]头部和胸部[5]可以融合在一起形成一个头胸部,[6]被一个大甲壳覆盖。[7]甲壳动物的身体受到坚硬外骨骼的保护,动物必须蜕皮才能生长。每个体节周围的壳可分为背背脊、腹胸骨和侧胸膜。外骨骼的不同部分可以融合在一起。[8]

每个体节有一对附肢:头部部分,包括两对触角,大颚和小颚;[3]胸段附肢又专门分为步足和颚足。[4]腹部是游泳足,[5]末端是尾节,尾节上有肛门,两侧尾足形成尾扇。[9]甲壳动物不同附肢的数量和种类在一定程度上可能是不同种群的原因。[10]

甲壳动物的附肢通常为双肢型,这意味着它们分为两部分;这包括第二对触角,但不包括第一对触角,第一对触角通常是单肢的,例外的是软甲纲,其触角通常可以是双肢型,甚至是三肢型。[11][12] 还不清楚双肢型状态是甲壳动物进化而来的衍生状态,还是肢体的第二个分支在所有其他群体中都消失了。例如,三叶虫也有双肢型附肢。[13]

主体腔是一个开放的循环系统,血液由位于背部附近的心脏泵入血腔。[14]软甲纲以血蓝蛋白为携氧色素,而桡足类、介形类、藤壶和鳃足类则有血红蛋白。[15]消化道由直管组成,直管通常有一个用来磨碎食物的类似鸡内金的“胃磨”和一对吸收食物的消化腺;这种结构呈螺旋形。[16]起肾脏作用的结构位于触角附近。大脑以靠近触角的神经节的形式存在,在肠道下面有一个主要神经节的集合。[17]

在许多十足类动物中,雄性动物第一对(有时是第二对)游泳足专门进行精子转移。许多陆生甲壳类动物(如圣诞岛红蟹)会季节性交配,然后回到海里产卵。其他动物,如木虱会条件潮湿在陆地上产卵。在大多数十足类动物中,雌性会留它们的卵,直到卵子孵化成自由游动的幼虫。[18]

2 生态学编辑

大多数甲壳类动物是水生的,生活在海洋或淡水环境中,但少数群体已经适应了陆地上的生活,如陆地蟹、陆地寄居蟹和木虱。海洋甲壳类动物在海洋中无处不在,就像昆虫在陆地上一样。[19][20] 大多数甲壳纲动物也是游动的,可以独立活动,尽管一部分种类的动物是寄生的,依附于他们的宿主生存(包括海虱、鱼虱、鲸虱、舌虫和缩头鱼虱,所有这些都可以被称为“甲壳纲虱子”),成年藤壶过着固着的生活——它们头朝下附着在基底上,不能独立活动。一些鳃尾类动物能够承受盐度的快速变化,也能从海洋物种宿主转换成非海洋物种宿主。[21]磷虾是南极动物群落食物链的底层和最重要的部分。一些甲壳类动物是显著的入侵物种,如中华绒螯蟹(Eriocheir sinensis)[22]和亚洲海岸蟹(Hemigrapsus sanguineus)。[23]

3 生存期编辑

3.1 交配方案

大多数甲壳动物有不同的性别,进行有性繁殖。[24]少数是雌雄同体,包括藤壶、桨足纲[25]和头虾纲。[26]有些动物甚至可能在一生中改变性别。[26]孤雌生殖在甲壳纲动物中也很普遍,在甲壳纲动物中,活卵由雌性产生,而不需要雄性受精。[24]这发生在许多鳃足类、一些介形类、一些等足类和某些“高等”甲壳类动物中,如大理石纹螯虾(Marmorkrebs)。

3.2 卵

在许多甲壳纲动物群体中,受精的卵被简单地释放到水体中,而其他动物则开发了许多机制来留住它们的卵直到它们准备孵化。大多数十足类动物将他们的卵附着在游泳足上,而囊虾总目、背甲目、无甲目和许多等足目动物从甲壳和胸肢形成一个孵卵袋[24]。雌性鳃尾亚纲动物不在外卵囊中携带卵,而是成排地将卵附着在岩石和其他物体上。[27]大多数薄甲类和磷虾在胸肢之间携带卵;一些桡足类在特殊的薄壁囊里携带它们的卵,而另一些桡足类将卵附着在一起成长长地、复杂的一串[24]

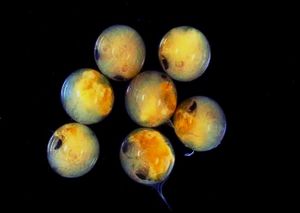

3.3 幼虫

甲壳类动物有许多幼体形式,其中最早和最具特征的是无节幼体。它有三对附肢,都来自幼小动物的头部,还有单个无节幼体眼。在大多数群体中,有更多的幼虫阶段,包括蚤状幼体。[28]赋予这个名字的时候,自然学家认为它是一个独立的物种时。[29]它在无节幼体阶段发生,先于后幼体,与无节幼体使用头部的附肢游泳不同,海蟹幼虫用胸部的附肢游泳,而大眼幼体使用腹部的附肢游泳。它的甲壳上经常有尖刺,这可能有助于这些小生物保持定向游泳。[30]在许多十足类动物中,由于它们的加速发育,蚤状幼体是第一个幼虫阶段。在某些情况下,蚤状幼体阶段之后是糠虾幼体阶段,而在另一些情况下,蚤状幼体阶段之后是是大眼幼体阶段,这取决于甲壳类动物种群。

4 分类编辑

“甲壳纲动物”这个名称追溯到最早描述动物的作品,包括皮埃尔·贝龙( Pierre Belon))和纪尧姆·朗德雷特(Guillaume Rondelet)的,但后来的一些作者没有使用这个名称,包括卡尔·林奈(Carl Linnaeus),他在《自然系统》中把甲壳纲动物归于“无翅目”中。[31]使用“甲壳纲”这个名称的最早合法命名是莫滕·萨尔内·布吕尼奇(Morten Thrane Brünnich)于1772年在创立的动物学基金会,[32]尽管他也将钳角亚门包括在这个纲中。[31]

甲壳亚门包括近67,000种描述的物种,[33]这被认为只是总数的十分之一到百分之一,因为大多数物种仍未被发现。[34]虽然大多数甲壳类动物都很小,但它们的形态差异很大,包括世界上最大的节肢动物——日本蜘蛛蟹,足展为3.7米(12英尺)[35]和最小的长100微米 (0.00004英寸)的Stygotantulus stocki。[36]尽管甲壳纲动物的形态多样,但它们都因为具有熟知的无节幼体的特殊幼体形态而归结为一体。

截至2012年4月,甲壳纲与其他分类群的确切关系尚未完全确定。基于形态学的研究产生的 “泛甲壳动物假说”,[37]假说指明甲壳纲动物和六足类动物(昆虫和同类)是姐妹类群。最近使用DNA测序的研究表明甲壳纲是并系类群,六足动物嵌套在一个更大的甲壳纲分支中。[38][39]

尽管甲壳纲动物的分类变化很大,马丁(Martin)和戴维斯(Davis)使用的系统[40]在很大程度上取代了早期的工作。须虾纲和鳃尾纲有时候分别各为一类对待,在这里被视为颚足纲的一部分。通常认定为六个纲:

| 纲 | 成员 | 目 | 影像图 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 鳃足纲 | 丰年虾 仙女虾 水蚤 蝌蚪虾 蛤虾 |

无甲目 弃甲目 背甲目 光尾叶肢介亚目 棘尾亚目 圆蚌虫亚目 枝角目 |

水蚤(枝角目) |

| 桨足纲 | 浆足目 | 现代桨足虫(斯氏浆足科) |

|

| 头虾纲 | 马蹄虾 | 短足目 | |

| 颚足纲 | 藤壶 桡足虫 |

哲水蚤目 长梗扁桃 无柄目 等其他20个 |

星状小藤壶(无柄目) |

| 介形纲 | 种子虾 | 壮肢目 海介虫目 简肢目 尾肢目 |

可代表筒柱萤科 |

| 软甲纲 | 蟹 龙虾 小龙虾 虾 磷虾 螳螂虾 木虱 涟虫 飞毛腿 砂蚤 等等。 |

十足目 等足目 端足目 口足目 等其他12个 |

钩虾属 (端足目) |

5 化石记录编辑

甲壳类动物有丰富而大量的化石记录,始于中寒武纪伯吉斯页岩,[41][42]比如加拿大虫和锐虾等动物。大多数甲壳类主要群体出现在寒武纪末期之前的化石记录中,也就是鳃足类、颚足纲(包括藤壶和舌虫)和软甲类;关于寒武纪中被分配到介形类的动物是否真的是介形类,还有一些争论,[43]否则这些动物可能会始于奥陶纪。后来出现的仅存的种类是头虾类[44],没有化石记录,浆足类最初是从金丝雀花化石描述的,但直到石炭纪才出现。[45]大多数早期甲壳类动物都很稀有,但是甲壳类动物化石从石炭纪开始就变得丰富起来。[41]

软甲纲化石没有磷虾的化石,[46]而掠虾亚纲和叶足亚纲都有现已灭绝的重要群体和现存成员(掠虾亚纲:螳螂虾现存,而奇泳目已灭绝;[47]叶足亚纲:加拿大虫目已经灭绝,而薄甲目现存)的化石。[42]涟虫目和等足目都是石炭纪的物种,[48][49] 第一只真正的螳螂虾也是如此。[50]在十足目动物中,明虾和多钳虾出现在三叠纪,[51][52] 虾和蟹出现在侏罗纪。[53][54] 蛇形化石洞穴是鬼虾造造成的,而拱形化石洞穴是小龙虾造成的。在努拉的二叠纪-三叠纪矿床上保存的最古老的(二叠纪: 罗德阶)河流洞穴,分别归属于鬼虾(十足目: 阿蟹科,虎鱼科)和小龙虾(十足目: 螯虾下目,副蝲蛄科)。[55]

然而,甲壳类动物的大爆发发生在白垩纪,尤其是蟹类,可能是由它们的主要捕食者硬骨鱼的大量扩张驱动的。[54]第一只真正的龙虾也出现在白垩纪。[56]

参考文献

- [1]

^Calman, William Thomas (1911年). "Crustacea" . In Chisholm, Hugh. 大英百科全书. 7 (第十一版 ed.). 剑桥大学出版社. p. 552. Check date values in: |year= (help).

- [2]

^Omar Rota-Stabelli; Ehsan Kayal; Dianne Gleeson; Jennifer Daub; Jeffrey L. Boore; Maximilian J. Telford; Davide Pisani; Mark Blaxter & Dennis V. Lavrov (2010). "Ecdysozoan Mitogenomics: Evidence for a Common Origin of the Legged Invertebrates, the Panarthropoda". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2: 425–440. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq030. PMC 2998192. PMID 20624745. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10..

- [3]

^"Cephalon". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [4]

^"Thorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [5]

^"Abdomen". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [6]

^"Cephalothorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [7]

^"Carapace". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [8]

^P. J. Hayward; J. S. Ryland (1995). Handbook of the marine fauna of north-west Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854055-7. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [9]

^"Telson". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [10]

^Elizabeth Pennisi (July 4, 1997). "Crab legs and lobster claws". Science. 277 (5322): 36. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.36..

- [11]

^"Antennule". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [12]

^"Crustaceamorpha: appendages". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [13]

^N. C. Hughes (February 2003). "Trilobite tagmosis and body patterning from morphological and developmental perspectives". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 185–206. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.185. PMID 21680423..

- [14]

^Akira Sakurai. "Closed and Open Circulatory System". Georgia State University. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [15]

^Klaus Urich (1994). "Respiratory pigments". Comparative Animal Biochemistry. Springer. pp. 249–287. ISBN 978-3-540-57420-0..

- [16]

^H. J. Ceccaldi. Anatomy and physiology of digestive tract of Crustaceans Decapods reared in aquaculture (PDF). Advances in Tropical Aquaculture. Tahiti Feb. 20 – March 4, 1989. AQUACOP, IFREMER. Actes de Colloque 9. pp. 243–259..

- [17]

^Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005). "Crustacean". Encarta. Microsoft..

- [18]

^Burkenroad, M. D. (1963). "The evolution of the Eucarida (Crustacea, Eumalacostraca), in relation to the fossil record". Tulane Studies in Geology. 2 (1): 1–17..

- [19]

^"Crabs, lobsters, prawns and other crustaceans". Australian Museum. January 5, 2010. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [20]

^"Benthic animals". Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [21]

^Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (1991). "Crustacea: Introduction and Peracarida". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates (1st ed.). Academic Press. pp. 665–722. ISBN 978-0-12-690645-5. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [22]

^Gollasch, Stephan (October 30, 2006). "Eriocheir sinensis" (PDF). Global Invasive Species Database. Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [23]

^John J. McDermott (1999). "The western Pacific brachyuran Hemigrapsus sanguineus (Grapsidae) in its new habitat along the Atlantic coast of the United States: feeding, cheliped morphology and growth". In Schram, Frederick R.; Klein, J. C. von Vaupel. Crustaceans and the biodiversity crisis: Proceedings of the Fourth International Crustacean Congress, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, July 20–24, 1998. Koninklijke Brill. pp. 425–444. ISBN 978-90-04-11387-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [24]

^"Crustacean (arthropod)". Encyclopædia Britannica..

- [25]

^G. L. Pesce. "Remipedia Yager, 1981"..

- [26]

^D. E. Aiken; V. Tunnicliffe; C. T. Shih; L. D. Delorme. "Crustacean". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [27]

^Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (2001). "Introduction to the Subphylum Crustacea". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich. Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 777–798. ISBN 978-0-12-690647-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [28]

^Zoea. 牛津英语词典 (第三版) (in 英语). 牛津大学出版社. 2001..

- [29]

^Calman, William Thomas (1911年). "Crab" . In Chisholm, Hugh. 大英百科全书. 7 (第十一版 ed.). 剑桥大学出版社. p. 356. Check date values in: |year= (help).

- [30]

^W. F. R. Weldon (July 1889). "Note on the function of the spines of the Crustacean zoœa" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1 (2): 169–172. doi:10.1017/S0025315400057994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17..

- [31]

^Lipke B. Holthuis (1991). "Introduction". Marine Lobsters of the World. FAO Species Catalogue, Volume 13. Food and Agriculture Organization. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-92-5-103027-1..

- [32]

^M. T. Brünnich (1772). Zoologiæ fundamenta prælectionibus academicis accomodata. Grunde i Dyrelaeren (in Latin and Danish). Copenhagen & Leipzig: Fridericus Christianus Pelt. pp. 1–254.CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link).

- [33]

^Zhi-Qiang Zhang (2011). Z.-Q. Zhang, ed. "Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness - Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848" (PDF). Zootaxa. 4138: 99–103..

- [34]

^"Crustaceans — bugs of the sea". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [35]

^"Japanese Spider Crabs Arrive at Aquarium". Oregon Coast Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [36]

^Craig R. McClain; Alison G. Boyer (June 22, 2009). "Biodiversity and body size are linked across metazoans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1665): 2209–2215. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0245. PMC 2677615. PMID 19324730..

- [37]

^J. Zrzavý; P. Štys (May 1997). "The basic body plan of arthropods: insights from evolutionary morphology and developmental biology". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 10 (3): 353–367. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1997.10030353.x..

- [38]

^Jerome C. Regier; Jeffrey W. Shultz; Andreas Zwick; April Hussey; Bernard Ball; Regina Wetzer; Joel W. Martin; Clifford W. Cunningham (February 25, 2010). "Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences". Nature. 463 (7284): 1079–1083. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1079R. doi:10.1038/nature08742. PMID 20147900..

- [39]

^Björn M. von Reumont; Ronald A. Jenner; Matthew A. Wills; Emiliano Dell'Ampio; Günther Pass; Ingo Ebersberger; Benjamin Meyer; Stefan Koenemann; Thomas M. Iliffe; Alexandros Stamatakis; Oliver Niehuis; Karen Meusemann; Bernhard Misof (March 2012). "Pancrustacean phylogeny in the light of new phylogenomic data: support for Remipedia as the possible sister group of Hexapoda". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (3): 1031–1045. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr270. PMID 22049065..

- [40]

^Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132..

- [41]

^"Fossil Record". Fossil Groups: Crustacea. University of Bristol. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [42]

^Derek Briggs (January 23, 1978). "The morphology, mode of life, and affinities of Canadaspis perfecta (Crustacea: Phyllocarida), Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 281 (984): 439–487. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.281..439B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0005..

- [43]

^Matthew Olney. "Ostracods". An insight into micropalaeontology. University College, London. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [44]

^Hessler, R. R. (1984). "Cephalocarida: living fossil without a fossil record". In N. Eldredge; S. M. Stanley. Living Fossils. New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-3-540-90957-6..

- [45]

^Stefan Koenemann; Frederick R. Schram; Mario Hönemann; Thomas M. Iliffe (12 April 2007). "Phylogenetic analysis of Remipedia (Crustacea)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 7 (1): 33–51. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2006.07.001..

- [46]

^"Antarctic Prehistory". Australian Antarctic Division. July 29, 2008..

- [47]

^Ronald A. Jenner; Cees H. J. Hof; Frederick R. Schram (1998). "Palaeo- and archaeostomatopods (Hoplocarida: Crustacea) from the Bear Gulch Limestone, Mississippian (Namurian), of central Montana". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (3): 155–186..

- [48]

^Frederick Schram; Cees H. J. Hof; Royal H. Mapes & Polly Snowdon (2003). "Paleozoic cumaceans (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) from North America". Contributions to Zoology. 72 (1): 1–16..

- [49]

^Frederick R. Schram (August 28, 1970). "Isopod from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois". Science. 169 (3948): 854–855. Bibcode:1970Sci...169..854S. doi:10.1126/science.169.3948.854. PMID 5432581..

- [50]

^Cees H. J. Hof (1998). "Fossil stomatopods (Crustacea: Malacostraca) and their phylogenetic impact". Journal of Natural History. 32 (10 & 11): 1567–1576. doi:10.1080/00222939800771101..

- [51]

^Robert P. D. Crean (November 14, 2004). "Dendrobranchiata". Order Decapoda. University of Bristol..

- [52]

^Hiroaki Karasawa; Fumio Takahashi; Eiji Doi; Hideo Ishida (2003). "First notice of the family Coleiidae Van Straelen (Crustacea: Decapoda: Eryonoides) from the upper Triassic of Japan". Paleontological Research. 7 (4): 357–362. doi:10.2517/prpsj.7.357..

- [53]

^Fenner A. Chace Jr. & Raymond B. Manning (1972). "Two new caridean shrimps, one representing a new family, from marine pools on Ascension Island (Crustacea: Decapoda: Natantia)". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 131 (131): 1–18. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.131..

- [54]

^J. W. Wägele (December 1989). "On the influence of fishes on the evolution of benthic crustaceans". Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 27 (4): 297–309. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1989.tb00352.x..

- [55]

^Baucon, A., Ronchi, A., Felletti, F., Neto de Carvalho, C. 2014. Evolution of Crustaceans at the edge of the end-Permian crisis: ichnonetwork analysis of the fluvial succession of Nurra (Permian-Triassic, Sardinia, Italy). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 410. Abstract available fromhttp://www.tracemaker.com.

- [56]

^Dale Tshudy; W. Steven Donaldson; Christopher Collom; Rodney M. Feldmann; Carrie E. Schweitzer (2005). "Hoploparia albertaensis, a new species of clawed lobster (Nephropidae) from the Late Coniacean, shallow-marine Bad Heart Formation of northwestern Alberta, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (5): 961–968. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0961:HAANSO]2.0.CO;2..

- [57]

^"FIGIS: Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2016-09-10..

- [58]

^Nicol, Steven; Endo, Yoshinari (1997). Krill Fisheries of the World. Fisheries Technical Paper. 367. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6..

暂无